Hi students,

As you all know, we're embarking on a new unit: To Kill A Mockingbird.

Here is an excerpt, taken directly from amazon.com:

"Shoot all the bluejays you want, if you can hit 'em, but remember it's a sin to kill a mockingbird."

A lawyer's advice to his children as he defends the real mockingbird of Harper Lee's classic novel—a black man charged with the rape of a white girl. Through the young eyes of Scout and Jem Finch, Harper Lee explores with rich humor and unswerving honesty the irrationality of adult attitudes toward race and class in the Deep South of the 1930s. The conscience of a town steeped in prejudice, violence, and hypocrisy is pricked by the stamina and quiet heroism of one man's struggle for justice—but the weight of history will only tolerate so much.

Grade Ten English Honors

Tuesday, February 14, 2012

Friday, November 4, 2011

An Interesting Blog...

While researching more information about our unit for In Cold Blood, I stumbled across this website. It asks some very pertinent questions that I want you to start thinking about...

http://cltlblog.wordpress.com/2008/12/31/reformative-literature-to-what-end/

http://cltlblog.wordpress.com/2008/12/31/reformative-literature-to-what-end/

Thursday, November 3, 2011

The Clutter House Today...

Hey crew,

Anthony also found this great photo of the Clutter house as it stood in 2009 (2 years ago). It still looks pretty similar.

You might not think that it looks like too much now, but back in the 50s a house like this would have been considered more than enough. Remember, the Clutters were in the expanding middle class, not the elite upper class.

Still, a house like this would have been more than comfortable for a family like theirs...

Anthony also found this great photo of the Clutter house as it stood in 2009 (2 years ago). It still looks pretty similar.

You might not think that it looks like too much now, but back in the 50s a house like this would have been considered more than enough. Remember, the Clutters were in the expanding middle class, not the elite upper class.

Still, a house like this would have been more than comfortable for a family like theirs...

Another Newspaper Article

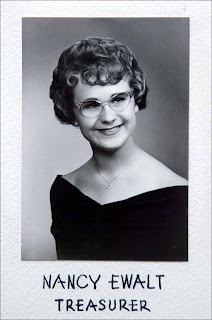

| Wichita Eagle (newspaper) SUNDAY November 14, 1999 Clutter murders still 'too close to home' for Holcomb residents Miniseries put details of murder in spotlight By Mark Wiebe Knight Ridder News Service HOLCOMB, Kan. --Taped inside Gary Jarmer's tattered first edition of "In Cold Blood" is a black-and-white photo of Jarmer standing next to Nancy Clutter, the youngest daughter of a wealthy and popular Finney County farmer. The teenagers proudly display the 4-H Who's Who Key Awards they won in the fall of 1958 for outstanding leadership. A year later, on Nov. 15, 1959, the bound bodies of Nancy; her father, Herb; her mother, Bonnie; and her younger brother, Kenyon, were discovered in their rural Holcomb, Kan., home. The four had been shot to death at close range. Jarmer would never again see or talk with the girl he had respected and admired, the energetic 16-year-old he had danced with on occasion, who one time told him, "Gary, you're a really good dancer." Like so many others who lived in this rural community 40 years ago, Jarmer felt the raw pain and shock of losing a friend. He and the community felt the fear of wondering why anyone (a neighbor? a stranger?) would want to kill such nice people. He felt the panic that drove many to buy new locks and some to put their loaded shotguns under their beds. For Jarmer, the deaths of the Clutters and feelings of loss were personal. They had not yet become part of the larger-than-life legend that this small Kansas farming community could have easily lived without. That would come later, in 1966, with the publication of Truman Capote's "In Cold Blood." Only then would the community's story be filtered through the eyes of a celebrated author who came across the Clutter name in a one-column article buried inside The New York Times. After enduring hordes of reporters, after having their pain splashed on the front pages of papers ranging from The Denver Post to The Kansas City Star, many Finney Countians thought their story reached a fitting conclusion on April 14, 1965. That is when the convicted killers, Perry Smith and Dick Hickock, climbed the gallows of the Kansas State Penitentiary in Lansing. The spotlight, they assumed, would go away, and those who knew the Clutters could choose their own way to grieve and remember, live and forget. Capote's so-called nonfiction novel wouldn't let them. Talk to friends or acquaintances of the Clutters, and many are likely to tell you they have not read the book or seen the film. Too close to home. Who, after all, wants to witness or imagine the violent deaths of people they knew? Who among them needs to hear again that Hickock and Smith went to Holcomb on an erroneous tip about piles of cash inside the Clutter home, and that they planned all along to leave no witnesses? But talk to the guardians of the area's two unofficial tourist destinations -- the old Clutter home and Valley View Cemetery in Garden City, where the Clutters are buried -- and you will discover that Capote's work has a firm purchase on America's collective imagination. Over the years, thousands have visited these two sites, neither of which appears on the historic walking or driving tours included in the Garden City and Holcomb Visitors Guide. "Basically, the only reason why people do come out here is because they've seen the movie or read the book," said Valley View's caretaker, Jim Hahn, standing just yards from the Clutters' headstones. "But 'In Cold Blood' just makes it really, really hard for those who are still alive." A cemetery employee for 24 years, Hahn said the curiosity-seekers were less abundant this year. "That's good," Hahn said, motioning to the headstones. "These people need to rest." Travel a few minutes west to Holcomb, and just about anyone in this town of 1,950 can direct you to the old River Valley Farm, 420 acres that Herb Clutter and his farmhands once tilled and harvested. Leonard and Donna Mader, both natives of the area, have owned the farm since 1990. Apart from a satellite dish perched above a window and the dusty rose aluminum siding around the second floor, the house looks much as it did 40 years ago, complete with neatly tuck-pointed tan bricks, and a large, flat yard of Bermuda grass in front. The property looks nothing like a tourist attraction. But, Donna Mader said, "there's always people calling me, 'Would you show us your home? Would you show us your home?' To me, it's just unreal." Mader said it was not uncommon on a summer weekend for as many as 10 cars to drive down the half-mile, elm-lined gravel drive just to stare at the house. Those numbers increased a few years ago after CBS broadcast a miniseries based on the book. "They're very nice people," she said. "From all over." Rarely do the Maders invite the curious in. But for a brief time they did give $5 tours. "Some of them almost begged to come in and see it, and I said, '...let's just let 'em,'" said Leonard Mader. The Maders stopped the tours after receiving letters they believed came from friends of the Clutters' two surviving daughters. How, Mader said the letter writers wanted to know, could they make money off the tragedy? Drive from the Mader house east to Main Street, turn left, cross the railroad tracks, and you will be staring down the closest thing resembling a downtown in Holcomb. But no one calls it that. There are no retail businesses on Main, just Holcomb Elementary School, the old vacant post office, a house that's for sale, a large field used by the school and the nondescript white building that houses El Rancho Cafe. In Wednesday's lunch at El Rancho, the talk at rancher Bob Jones' table was sports. The eight men, including Jones, said they had not realized the anniversary of the murders was approaching. Jones, 56, who knew Nancy Clutter, said, "I'm not too keen on talking about it." Duane West, the man who helped prosecute Hickock and Smith, is not as reticent. He will reflect on the tragedy of having lost "the productive intellect and capacity" of the victims, with whom West attended church. But he did not see the newsworthiness in the 40th anniversary. So many people, he said, have moved to the area since the killings, several thousand attracted by jobs at two large slaughterhouses built in the 1980s. "I think it's basically a nonevent for the community....We've got a lot who never even heard of the murders. Many probably don't even know who Truman Capote was," West said. Jarmer, grayer and heavier than he appears in the snapshot with Nancy Clutter, stood outside the Finney County Courthouse on Wednesday. It's the same building he twice entered as an 18-year-old farm boy to attend Hickock's and Smith's trial. Holding his copy of "In Cold Blood" , Jarmer recalled the crisp fall morning when he and a friend, just back from pheasant hunting, sat stunned in a pickup truck as the news broke on radio station KIUL. He talked about Nancy and Kenyon. A rueful look came over his face. "They were cut down way, way too early," said Jarmer, who retired as a dean at Garden City Community College in 1998. "I got to live my life, and they didn't." Even though he lived through the events 40 years ago, Jarmer believes Capote's work serves as a valuable document for those who were not there at the time. His 32-year-old son, Mark, a history instructor at the college who studied the murders two years ago to prepare for a course on Kansas literature, agrees. As part of the course, Mark Jarmer took students to the Mader house. He showed them the seven blue, loose-leaf notebooks in the Finney County Sheriff's Department -- notebooks with documents from the case, newspaper clippings and crime scene photos. Jarmer's course and the notebooks, assembled in the last two years, are signs that some in the community are beginning to accept their place in history. So is the Garden City Police Department's glass-enclosed case that displays, among other things, Perry Smith's black leather boot, some of the rope the killers used, a copy of "In Cold Blood" and a Life magazine article about the movie. It's doubtful that the likes of Bob Jones will ever view these artifacts. But the years to come will leave fewer who lived through that crisp November morning, and more who will experience it only through Capote's literary lens or the movies it spawned. Those people will be curious. |

Newspaper Article

Wichita Eagle (newspaper)

November 25, 1996

Thirty-seven years after the murders of a family of four in a quiet Kansas town, fascination with the case continues.

'In Cold Blood'

Miniseries renews focus on Holcomb

A family of four was killed at this house in Holcomb in 1959. People still travel to the site of the murders, which Truman Capote wrote about in the book "In Cold Blood."

By L. Kelly, Jennifer Comes Roy and Michele Chan Santos

Jane LiaKos, a computer operator and the woman who answers the phone

"all the time" in the Holcomb City Building, was hardly surprised to get a call from a Wichita reporter Friday morning.

She has answered calls from a lot of reporters recently, "mostly from

newspapers questioning how people feel about 'The Movie'."

"The Movie," of course, is "In Cold Blood," the new CBS miniseries that retells the story of the Clutter murders in 1959. Part one of the movie aired last night; it concludes Tuesday night.

In the early hours of Nov. 15, 1959, Herbert and Bonnie Clutter and two of their teenage children were shot to death in their farmhouse on the edge of Holcomb. Their killers -- Perry Smith and Dick Hickock -- had hoped to find a safe stuffed with cash in the home. It didn't exist; they ended up taking $43, a pair of binoculars and a radio.

Thirty-seven years later, Holcomb, a few miles west of Garden City on

Highway U.S. 50, is still best known for the tragedy.

The town -- especially the Clutter home on Oak Avenue -- has been a

tourist attraction for the curious for years. In the past few weeks, as the miniseries has been advertised by CBS, LiaKos and others have taken a lot of calls from people asking where the house is.

The residents of Holcomb are more concerned about whether the miniseries "will be far-fetched or true to life," LiaKos said.

"Interest hasn't died because it happened in such a small town . . . and they were such a well-liked, common-folk family," she said. In addition to their daughter Nancy, 16, and son Kenyon, 15, who were killed, the Clutters had two grown daughters who no longer live in the Holcomb area.

Around town, talk about the case "goes in spells," LiaKos said. Even

without media attention, "about this time of year, it is in the back of peoples' minds."

The remake "bothers some people," she said. "Especially those who lived here at the time. It brings the memories back.

"To me, it's not a big deal," LiaKos said. "Of course, I didn't know the family."

Actually, LiaKos said, she hadn't even heard of the murders before

moving from Nebraska to Holcomb about a dozen years ago.

Reading stories about the murders on the 25th anniversary was disturbing, but not enough to prevent her from staying.

The murders were a long time ago, and are a part of the town's history

that residents have grown to accept.

"Holcomb is small enough, everybody lives near Oak Street . . . within

six or seven blocks, anyway," LiaKos said.

"The trees are still there," she said, referring to a famous scene at

the farm in the 1967 black-and-white film. "Driving down the road at the end of the lane is just like the movie. It's kind of creepy."

Although Holcomb's population has grown from about 300 in 1959 to nearly 2,000 now, the Clutter house is still isolated, still surrounded by fields.

Back in 1990, the new owners of the Clutter house, Leonard and Donna

Mader, were pestered so frequently by strangers wanting to see the house that they decided to open it up for $5 tours on weekends.

People came from across the country -- and from several other countries as well.

When news stories started popping up about the tours, the Maders were

criticized for trying to capitalize on a tragedy.

They stopped giving tours shortly after that. And though "a lot of

people come," Leonard Mader said, "We don't let them in the house anymore." They've gotten used to people pulling into the driveway for a quick peek at the outside of their house, despite the "No Trespassing" sign.

Mader expects to see a surge in visits from the curious in the wake of

the miniseries.

In advance of the remake's television debut, the Maders have been

besieged by calls from reporters.

"CBS called. People magazine called. Everybody in the country called,"

Leonard Mader said. "I've done so many interviews I can't even talk."

Mader said he's gotten used to the attention the house attracts. But

it's still his home. "It's a pretty house, a big house," Mader said. "Everybody likes the way it's laid out."

Mader also met actor Sam Neill, who plays KBI investigator Alvin Dewey

in the miniseries. Although the miniseries was filmed in Canada, Neill came to Holcomb for a day and toured the house.

"He was a real nice guy," Mader said.

The real-life Dewey, who died in 1987, was never comfortable with the

attention he received after Truman Capote's book and the 1967 movie highlighted his role in the killers' capture.

Lanny Grosland, special agent in charge of the Kansas Bureau of

Investigation's Wichita region, took over as head of the KBI's Garden City office about two years before Dewey retired in 1975.

"The first time I met him was in new agent's school and I couldn't wait to meet Al Dewey in person," Grosland said. "I was a little disappointed because he was a little shorter than the guy in the movie."

Dewey's picture and some of the evidence collected by KBI agents in the

Clutter investigation are still prominently displayed at KBI headquarters in Topeka, he said. Dewey knew the Clutter case was the most notorious he'd worked on, but he didn't consider it the most difficult, Grosland said.

"He was just kind of an average guy; he always impressed me as being

just a real gentleman, slow-spoken," Grosland said. " . . . He was just an old cop."

Dewey always pointed out that he was just one of four KBI agents

investigating the Clutter murders, and that other law enforcement agencies played an active part in the investigation.

But as he wrote the book, Capote's focus on Dewey tightened -- probably because he was in charge of the KBI's Garden City office; probably also because Dewey knew Herb Clutter.

Capote, who lived in Kansas for six years researching his book, "was a

little strange, even for Wichita, and it goes without saying he was strange for Garden City," Grosland said. Dewey "took Truman Capote in and treated him nice, and Capote probably just liked him for that."

Robert Clester, a retired special agent in charge of investigations for the KBI, worked with Dewey for several years. He agreed that the limelight was not something that Dewey sought out while involved in the Clutter investigation.

"Mostly, he was wanting just to solve the case, not wanting publicity

for himself," he said. "He had known the Clutters and it became something he just had to solve."

November 25, 1996

Thirty-seven years after the murders of a family of four in a quiet Kansas town, fascination with the case continues.

'In Cold Blood'

Miniseries renews focus on Holcomb

A family of four was killed at this house in Holcomb in 1959. People still travel to the site of the murders, which Truman Capote wrote about in the book "In Cold Blood."

By L. Kelly, Jennifer Comes Roy and Michele Chan Santos

Jane LiaKos, a computer operator and the woman who answers the phone

"all the time" in the Holcomb City Building, was hardly surprised to get a call from a Wichita reporter Friday morning.

She has answered calls from a lot of reporters recently, "mostly from

newspapers questioning how people feel about 'The Movie'."

"The Movie," of course, is "In Cold Blood," the new CBS miniseries that retells the story of the Clutter murders in 1959. Part one of the movie aired last night; it concludes Tuesday night.

In the early hours of Nov. 15, 1959, Herbert and Bonnie Clutter and two of their teenage children were shot to death in their farmhouse on the edge of Holcomb. Their killers -- Perry Smith and Dick Hickock -- had hoped to find a safe stuffed with cash in the home. It didn't exist; they ended up taking $43, a pair of binoculars and a radio.

Thirty-seven years later, Holcomb, a few miles west of Garden City on

Highway U.S. 50, is still best known for the tragedy.

The town -- especially the Clutter home on Oak Avenue -- has been a

tourist attraction for the curious for years. In the past few weeks, as the miniseries has been advertised by CBS, LiaKos and others have taken a lot of calls from people asking where the house is.

The residents of Holcomb are more concerned about whether the miniseries "will be far-fetched or true to life," LiaKos said.

"Interest hasn't died because it happened in such a small town . . . and they were such a well-liked, common-folk family," she said. In addition to their daughter Nancy, 16, and son Kenyon, 15, who were killed, the Clutters had two grown daughters who no longer live in the Holcomb area.

Around town, talk about the case "goes in spells," LiaKos said. Even

without media attention, "about this time of year, it is in the back of peoples' minds."

The remake "bothers some people," she said. "Especially those who lived here at the time. It brings the memories back.

"To me, it's not a big deal," LiaKos said. "Of course, I didn't know the family."

Actually, LiaKos said, she hadn't even heard of the murders before

moving from Nebraska to Holcomb about a dozen years ago.

Reading stories about the murders on the 25th anniversary was disturbing, but not enough to prevent her from staying.

The murders were a long time ago, and are a part of the town's history

that residents have grown to accept.

"Holcomb is small enough, everybody lives near Oak Street . . . within

six or seven blocks, anyway," LiaKos said.

"The trees are still there," she said, referring to a famous scene at

the farm in the 1967 black-and-white film. "Driving down the road at the end of the lane is just like the movie. It's kind of creepy."

Although Holcomb's population has grown from about 300 in 1959 to nearly 2,000 now, the Clutter house is still isolated, still surrounded by fields.

Back in 1990, the new owners of the Clutter house, Leonard and Donna

Mader, were pestered so frequently by strangers wanting to see the house that they decided to open it up for $5 tours on weekends.

People came from across the country -- and from several other countries as well.

When news stories started popping up about the tours, the Maders were

criticized for trying to capitalize on a tragedy.

They stopped giving tours shortly after that. And though "a lot of

people come," Leonard Mader said, "We don't let them in the house anymore." They've gotten used to people pulling into the driveway for a quick peek at the outside of their house, despite the "No Trespassing" sign.

Mader expects to see a surge in visits from the curious in the wake of

the miniseries.

In advance of the remake's television debut, the Maders have been

besieged by calls from reporters.

"CBS called. People magazine called. Everybody in the country called,"

Leonard Mader said. "I've done so many interviews I can't even talk."

Mader said he's gotten used to the attention the house attracts. But

it's still his home. "It's a pretty house, a big house," Mader said. "Everybody likes the way it's laid out."

Mader also met actor Sam Neill, who plays KBI investigator Alvin Dewey

in the miniseries. Although the miniseries was filmed in Canada, Neill came to Holcomb for a day and toured the house.

"He was a real nice guy," Mader said.

The real-life Dewey, who died in 1987, was never comfortable with the

attention he received after Truman Capote's book and the 1967 movie highlighted his role in the killers' capture.

Lanny Grosland, special agent in charge of the Kansas Bureau of

Investigation's Wichita region, took over as head of the KBI's Garden City office about two years before Dewey retired in 1975.

"The first time I met him was in new agent's school and I couldn't wait to meet Al Dewey in person," Grosland said. "I was a little disappointed because he was a little shorter than the guy in the movie."

Dewey's picture and some of the evidence collected by KBI agents in the

Clutter investigation are still prominently displayed at KBI headquarters in Topeka, he said. Dewey knew the Clutter case was the most notorious he'd worked on, but he didn't consider it the most difficult, Grosland said.

"He was just kind of an average guy; he always impressed me as being

just a real gentleman, slow-spoken," Grosland said. " . . . He was just an old cop."

Dewey always pointed out that he was just one of four KBI agents

investigating the Clutter murders, and that other law enforcement agencies played an active part in the investigation.

But as he wrote the book, Capote's focus on Dewey tightened -- probably because he was in charge of the KBI's Garden City office; probably also because Dewey knew Herb Clutter.

Capote, who lived in Kansas for six years researching his book, "was a

little strange, even for Wichita, and it goes without saying he was strange for Garden City," Grosland said. Dewey "took Truman Capote in and treated him nice, and Capote probably just liked him for that."

Robert Clester, a retired special agent in charge of investigations for the KBI, worked with Dewey for several years. He agreed that the limelight was not something that Dewey sought out while involved in the Clutter investigation.

"Mostly, he was wanting just to solve the case, not wanting publicity

for himself," he said. "He had known the Clutters and it became something he just had to solve."

A Word From The Surviving Clutters...

Students,

I found this while I was searching for more information on the Clutter Family.

http://www2.ljworld.com/news/2005/apr/04/sisters_family_surviving/

I found this while I was searching for more information on the Clutter Family.

http://www2.ljworld.com/news/2005/apr/04/sisters_family_surviving/

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)